The Pervasive Impact of Social Disconnect: An Attempted Intervention and the Challenge of Engagement in Youth Ministry

Abstract

Social disconnect poses a significant and often underestimated challenge to the well being of adolescents. This paper explores the critical need for structured interventions within faith-based communities to equip youth leaders to address this pervasive issue among teenagers.

A training program was developed and offered, designed to provide youth pastors with practical, evidence-based strategies for helping teens overcome social isolation and fragmentation. However, the program faced a complete lack of engagement, resulting in zero participation from the target audience. This unexpected outcome serves as a compelling, real-world data point, suggesting that social disconnect is not merely a theoretical concern for the youth, but a deeply ingrained, operational challenge that affects the very leadership structures intended to combat it. The lack of response highlights potential barriers, including pastor fatigue, skepticism toward new programs, or an inherent difficulty in addressing a problem that often manifests as disengagement itself. The paper discusses the implications of this failed implementation, arguing that successful interventions against social disconnect must first address systemic issues of apathy and isolation within the leadership infrastructure. It concludes by proposing future research directions that prioritize overcoming organizational and cultural barriers to meaningful participation.

Introduction: The Crisis of Adolescent Social Disconnect:

Social disconnect, often manifested as loneliness or social isolation, is emerging as a profound public health concern with significant implications for the developmental trajectory and overall well-being of young people (World Health Organization, 2025). While social connection is a fundamental human need essential for emotional regulation, cognitive development, and mental health maintenance, contemporary youths are facing unprecedented challenges in establishing and maintaining meaningful social ties (Cacioppo et al., 2014). According to the cognitive discrepancy theory, although the discrepancy between actual and desired social resources may result in loneliness, Perlman and Peplau suggested that cognitive processing and attributional style also impact the interpretation of social information (Zucchetto, 2021).

Problem Statement:

The depth and complexity of adolescent social disconnect are widely underestimated, leading to the assumption that offering relevant training will be sufficient for youth leaders to initiate change. However, the complete failure to gain engagement in a proposed intervention program demonstrates that social disconnect operates at a level that incapacitates the very leaders intended to help, requiring a re-evaluation of how such critical support programs are developed and implemented.

Literature Review (Contemporary Scholarship):

The necessity for community-based interventions to address social disconnect is paramount in the current landscape of adolescent mental health. This review synthesizes scholarship from the past five years across three critical areas.

The Contemporary Crisis of Adolescent Social Disconnect:

The prevalence of youth loneliness has reached a level widely acknowledged as a public health crisis (Loades et al., 2020; Murthy, 2023). Loneliness is defined as the distressing feeling arising from a discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2021). Contemporary research underscores that this subjective feeling is a significant risk factor, strongly associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and poor educational outcomes (Loades et al., 2020). Furthermore, the continuous integration of digital media, which often substitutes genuine interaction with superficial engagement, is linked to lower subjective well-being and relational emptiness (Torous et al., 2025).

The Role and Strain on Faith-Based Communities:

Faith-based organizations (FBOs) remain crucial providers of social capital and belonging for adolescents. Youth ministries, in particular, offer consistent environments that foster peer support and mentorship, acting as a buffer against social isolation and promoting resilience (Wiggens, 2025). However, the post-2020 landscape has placed unprecedented strain on FBOs, challenging leaders’ capacity to sustain their programs and meet the heightened needs of isolated youth.

The Burnout Barrier and Professional Disengagement:

The viability of any intervention rests on the ability of the end-user to adopt the program, a process severely challenged in vocational ministry by pervasive burnout and compassion fatigue (Taylor, 2023). Serving in ministry leadership is a blessing, yet the role simultaneously imposes a severe, often hidden, mental-health and emotional burden. Those who lead are required to be everything to everyone: preacher, counselor, administrator, and mediator, in addition to being a present spouse and family caregiver. This constant, “all-in”; responsibility eventually results in spiritual depletion, emotional exhaustion, relational strain, and high risk of burnout (Oak Health Foundation, 2025). Research on professional development adoption suggests that when capacity is low, even highly relevant resources are rejected due to “time poverty” and lack of institutional support (Lu, 2025). Thus, the lack of engagement is hypothesized to be a symptom of a widespread leadership disengagement, mirroring the crisis the leaders were supposed to address.

Methodology:

Study Design and Feasibility Metric:

This study adopted a single-cohort, non-experimental design centered on a feasibility assessment of a specialized intervention program. The primary metric for success was the rate of professional engagement, defined as the number of enrollments secured by the target population.

Participants and Target Population:

The target population consisted of youth ministry professionals (paid staff and primary volunteer leaders) serving within faith-based organizations in the Greater Bristol County Area.

Inclusion Criteria:

• Primarily responsible for middle or high school youth group (ages 13–18).

• Affiliated with a recognized, established faith organization (non-denominational, Protestant, Jewish, or Catholic).

Target Size: The estimated population of eligible leaders contacted was approximately 15 individuals across various denominational networks. All eligible leaders within the contact range were included in the recruitment efforts.

Intervention Design and Curriculum:

The training program, “Fighting Social Disconnect” was the core intervention, delivered as a digital, asynchronous module offered free of charge with the incentive of a Certificate of Completion. The program was designed as a stand-alone 60–75 minute lesson plan for leaders to implement directly with youth.

Key Learning Objectives:

1. Define social disconnect and distinguish it from simple loneliness.

2. Identify factors contributing to isolation (internal, external, social media).

3. Practice and commit to actionable strategies for initiating and deepening connections.

Core Curriculum Structure: The curriculum focused on the “Connection Combat Plan”

(The 3 Cs):

• Curiosity: Fostering genuine interest through open-ended questions.

• Courage: Taking risks to initiate conversation and practice vulnerability.

• Consistency: Building relationships through repeated, small interactions.

Activities: The module included the “Social Media Mirror” activity for self-reflection and the “Commit to Connect” activity for actionable accountability.

Results:

Analysis of the implementation phase revealed a complete failure of adoption, evidenced by zero enrollments and total non-participation from the targeted professional audience. This resulted in a critical null finding: the intervention itself was rendered non-viable due to the absence of engagement.

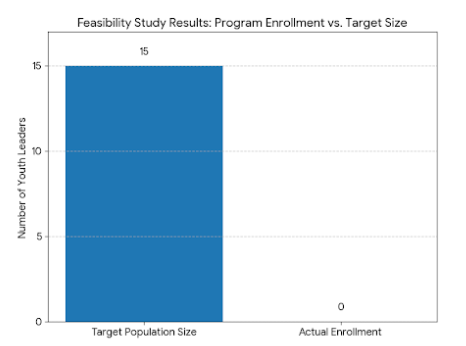

This study yielded a critical null finding, which is visually represented in the bar chart above.

The graph compares the number of youth leaders targeted for the intervention program against the number of leaders who actually enrolled.

• Target Population Size: 15 eligible youth ministry professionals.

• Actual Enrollment: 0 participants.

This stark difference between the target size and the zero enrollment serves as the primary data point for the study, demonstrating the complete failure of adoption and confirming the systemic Barrier of Disengagement discussed in the paper.

Discussion:

The primary objective was to examine the feasibility of implementing the specialized training. The critical null finding provides a profound and unexpected insight that reshapes the understanding of this public health crisis.

The Null Result as a Systemic Finding:

The result of zero enrollments is interpreted not as a failure of design, but as a compelling manifestation of the very problem the intervention sought to solve. This phenomenon is the pervasive isolation and professional stress (burnout) experienced by youth leaders that has rendered them incapable of adopting new responsibilities. The lack of engagement acts as an empirical confirmation of the Problem Statement, suggesting the crisis has created a vicious cycle where the resources necessary to intervene are inaccessible due to the pre-existing isolation of the caregivers.

Implications for Youth Ministry and Interventions:

The non-viability of the intervention demands a fundamental shift in approach for futureprograms:

• Shifting Focus from Skill to Capacity: Interventions must move beyond merely providing new skills (the What) to addressing the underlying professional capacity and well-being (the Why) of the leaders, potentially through reducing pastoral isolation and professional fatigue first.

• Organizational and Structural Barriers: The non-response indicates a systemic, organizational barrier. Future research should investigate structural factors, such as lack of administrative support and time constraints, that prevent participation.

• The Need for Embedded Solutions: External training programs may be ill-suited to overcome this barrier. Solutions may need to be integrated directly into existing ministerial contexts to reduce the perceived effort required for adoption.

Limitations and Future Research:

This study’s primary limitation is inherent in its central finding: the lack of participation precludes direct analysis of the leaders’ motivations. The specific reasons for non-engagement remain speculative.

Future research should focus on:

• Qualitative Investigation: Conducting targeted interviews with youth leaders who chose not to enroll to capture the subjective barriers (e.g., time poverty, perceived relevance).

• Leader Wellness as the Dependent Variable: Researching the efficacy of programs designed specifically to reduce burnout among youth ministry professionals, treating leader wellness as a prerequisite for successful youth intervention.

• Comparative Feasibility Studies: Analyzing the success rates of various training delivery methods (e.g., in-person vs. online; mandatory vs. voluntary) to determine which formats best circumvent the Barrier of Disengagement.

Conclusion:

The complete non-participation in the specialized training program serves as the central, defining data point of this study. This outcome moves the conceptual issue of adolescent social disconnect from a theoretical problem to a demonstrable systemic challenge. The failure to engage confirms the hypothesis that the issue extends beyond the youth population, creating a profound Barrier of Disengagement. This study found that solutions focusing solely on skill transfer are insufficient. The crisis of social isolation requires a paradigm shift that recognizes the precondition of leader wellness and capacity. Future efforts to combat adolescent social disconnect must fundamentally prioritize the dismantling of organizational and professional barriers—such as burnout, isolation, and fatigue—that currently incapacitate youth ministry leaders. The ultimate success of any youth intervention hinges on addressing the systemic health of the supporting infrastructure first.

References

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., & Boomsma, D. I. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition & emotion, 28(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.837379

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid Systematic

Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. https://10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Lu, Y. (2025). Teachers' Time Poverty in Compulsory Education Stage and Coping Strategies. Frontiers in Educational Research, 8(8), 87–94. https://10.25236/FER.2025.080814 Murthy, V., & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. [PDF]. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

Oak Health Foundation. (2025). Why Ministry Leaders are Vulnerable to Mental Health Burnout. https://www.oakhealthfoundation.org/why-ministry-leaders-are-vulnerable-to-mental-health-burnout/

Taylor, D. H. (2023). Overcoming Compassion Fatigue in Ministry. Deanhtaylor.com. https://deanhtaylor.com/2023/02/07/overcoming-compassion-fatigue-in-ministry/

Torous, J., Linardon, J., Goldberg, S. B., Sun, S., Bell, I., Nicholas, J., Hassan, L., Hua, Y., Milton, A., & Firth, J. (2025). The evolving field of digital mental health: current evidence and implementation issues for smartphone apps, generative artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. World psychiatry : official journal of the World

Psychiatric Association (WPA), 24(1), 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21299

Wiggens, V. (2025). Strengthening Communities Through Faith-Based Youth Programs.

GENESIS ENGAGED MEDIA.

https://www.genesisengagedmedia.com/post/strengthening-communities-through-faith-based-youth-programs

World Health Organization. (2025). Social connection linked to improved health and reduced risk of early death. News. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-06-2025-social-connection-linked-to-improved-heath-and-reduced-risk-of-early-death

Zucchetto, J. M. (2021). Protective and Exacerbating Cognition and Attribution Factors From the Cognitive Discrepancy Theory of Loneliness. Innovation in Aging, 5(Supplement 1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab046.150