Addressing Social Disconnection and Loneliness in Muslim Youth Groups: A Coregulation Approach

Background

Mental health has become a popular topic of discussion since the COVID-19 pandemic. While life outside came to a halt during the lockdown, life at home began to highlight issues that had been suppressed by the hustle and bustle of daily life. The lockdown gave those struggling with mental health a voice through social media, allowing them to share their experience and destigmatize the conversation surrounding mental health. As mental health became a socially acceptable subject, new research and approaches arose to address and resolve its related issues. Anxiety and depression became popular topics of concern, with professionals promoting therapy and advocating for testing and medication. A topic that seemed to stay away from the limelight was social disconnection, or isolation. Similarly, while this issue was exacerbated by the pandemic and even began to develop in patients as a result of the pandemic, the issue of loneliness was not given as much attention as anxiety and depression. Loneliness is a global health epidemic that affects an estimated 17% of US adults aged 18 to 70 and is linked to a 30% increase in heart disease, stroke, dementia, depression, and anxiety (Shah and Househ, 2023). The numbers are far greater for the younger individuals, with 50.8% of people aged 16 to 24 reporting feeling lonely compared to the general population ratio of 30.9% post-pandemic (Stickley et al., 2014). Even with the research present on loneliness and its effects, there is little work done to specifically tackle this issue.

Although community engagement programs exist that encourage community-wide engagement to promote mental health, initiatives that tackle loneliness and social disconnection are fewer in number than other mental health programs. One initiative that researches, provides training and education, and helps patients face loneliness and social disconnection, is Coregulation Health Institute. Coregulation Health Institute (CHI) is a program led by Dr. Robert Metcalf, PhD, that aims to improve public mental health through a process known as “coregulation”, which can be compared to active listening. CHI defines social disconnection as an objective state where there is a lack of social interactions, relationships, or connections, signifying an absence of social networks and support systems, irrespective of an individual's feelings about it. Loneliness, on the other hand, is defined as a subjective emotional state characterized by feelings of sadness and isolation due to a perceived lack of meaningful social connections (CHI, 2025). The aim of CHI is to utilize coregulation as a means of restoring coherence to the Polyvagal nervous system while confronting social disconnection and loneliness.

As mentioned previously, the youth are more prone to loneliness and social disconnection. Though this is an issue that affects every child, it is also important to understand that a child’s background can also affect their vulnerability. Specifically, religion can play a major role in how a child perceives their mental health and what is done to address it. Religion is often treated as a culture rather than a way of life, which is why it varies per person and per family, since culture is open for interpretation. Despite the fact that Islam addresses loneliness and social disconnection in its basic principles, there are essentially no efforts globally that outright confront this issue in the Muslim community. With that being said, far less research is done regarding Muslim youth. Like many communities, Muslim youth groups exist to empower the youth, teach them the basics of brotherhood, sisterhood, and community, and bring them closer to the religion. With that being said, perhaps these spaces can be used to address issues regarding loneliness and social disconnection as well.

Statement of Problem

As mentioned previously, loneliness and social disconnection are harmful to human health. Demographic groups affected severely in the US include seniors, students, medical patients, and military veterans.

Students, or the youth, are experiencing significantly higher rates of suicide and mental illness (depression, anxiety, drug abuse, suicidal ideation) related to loneliness and social disconnection.

Literature Review

The literature review focuses on identifying programs and studies aside from the Coregulation Health Institute that tackle social disconnection and loneliness in the youth. It then transitions to determine if similar approaches have been used for a Muslim population. Ultimately, it prioritizes identifying efforts that address social disconnection and loneliness in the Muslim youth.

A review of the opportunities and challenges for loneliness interventions by Hurmat A. Shah and Mowafa Househ states that there are distinct causes of loneliness and isolation in the youth that should be addressed with the corresponding distinct approaches. While this review cites psychological approaches such as reminiscence therapy (Chiang et al., 2010), mindfulness-based stress reduction training (Creswell et al., 2012), and community-based health promotion programs (Collins and Benedict, 2006), these approaches have been made specifically for the elderly and do not account for the youth. However, the review does cite a study on digital humans delivering psychological therapies through the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic for participants aged 18-69. While this does not specifically address the youth, the study did see that the digital human interventions and trial methods were generally found to be feasible and acceptable in younger and older adults living independently (Loveys et al., 2021). This implies that technological interventions to loneliness and social disconnection can be applied to the youth, since technology is easily accessible to most in the US, and this method proved to be feasible for young adults; perhaps it could be applied to the youth as well (Shah and Househ, 2023).

Furthermore, an article on identifying and addressing loneliness in Generation Z and Generation Alpha recommends four family-based intervention strategies, citing the principles of Narrative and Strategic Family Therapy as the rationale behind the effectiveness of these interventions (Wooley, 2025). While these interventions have strong scientific evidence behind them, with only one piece of evidence testing these interventions, it is difficult to assess the applicability of these interventions in a universal setting. Lastly, a review approaching the youth on how they perceive loneliness and feasible methods of intervention found that the youth believed different approaches were necessary for different levels of loneliness. They emphasized the importance of ensuring each approach was appealing to the target age group to ensure 100% participation, suggesting that interventions be co-produced by members of that age group (Eager et al., 2024). This proves to have the strongest credibility compared to previous articles and studies since it focuses specifically on the youth, it engages youth from various backgrounds to collect accurate and applicable data, and it produces usable data.

Moving on to isolation and loneliness interventions in the Muslim community, data is primarily from the UK and Canada. While research is limited, a Canadian study on Muslim immigrants found that isolation was a major factor in poor aging in the elderly (Salma and Salami, 2020). Other information regarding loneliness in the Muslim community includes sites that encourage behavioral changes, such as a healthy diet and exercise in combination with group therapy and attending community events (Khorram, 2025).

Finally, there is little to no information regarding loneliness and isolation interventions in the Muslim youth. While coping mechanisms and strategies exist for Muslims online, little is done to help the youth address loneliness and isolation. This study aims to fill the gap in the literature that exists to address loneliness and social disconnection in Muslim youth.

Hypothesis

Muslim community youth groups can be empowered by education and training to adopt proven public health programs and services from Coregulation Health Institute that alleviate student loneliness and social disconnection.

Methodology

Using a qualitative interview design, research was conducted over the course of eight weeks, commencing by emailing a background on the Coregulation Health Institute to the Islamic Center of Naperville (ICN) in Naperville, Illinois. Once the mosque responded by expressing interest in the program, an interview was scheduled and conducted. The interview consisted of the questions, “In your experience, how does the epidemic of loneliness and social disconnection affect the youth in your community?” and “What programs and activities do you offer to protect students against harm from loneliness and social disconnection?”.

Simultaneously an email sharing information on Coregulation Health Institute with an attached infographic poster covering Coregulation Health Institute’s mission (Figure 1) was sent to five mosques in DuPage County, Illinois, including the Islamic Center of Wheaton (ICW) in Wheaton, Illinois, the Islamic Foundation School (IFS) in Villa Park, Illinois, Darussalam and Masjid Uthman in Lombard, Illinois, and the Mecca Center in Willowbrook, Illinois. This email was also sent to two mosques in Cook County, Illinois, including the Islamic Community Center of Des Plaines (ICCD) in Des Plaines, Illinois, and the Muslim Education Center (MEC) in Morton Grove, Illinois. This email asked youth leaders the following two questions: “Are you interested in information about programs and services that alleviate student loneliness and social disconnection?” and “Are you interested in participating in a Youth Pastor’s National Discussion on How to Protect Our Youth Against the Epidemic of Loneliness and Social Disconnection?”.

From here, an experiment was designed to determine if the Christian Youth Group lesson plan from Coregulation Health Institute could be applied in a Muslim youth group setting. A four-week lesson plan was designed for the ICN after-school program for middle school girls, which included a lesson on social disconnection and loneliness, as well as an exercise on coregulation. The number of participants varied per week, ranging from a minimum of 60 to a maximum of 80 girls. The participants’ ages ranged from 10 to 14 years old, from various middle schools, as well as a handful of homeschooled students. The lesson plan and resources were shared with ICN, and once approved, the experiment began.

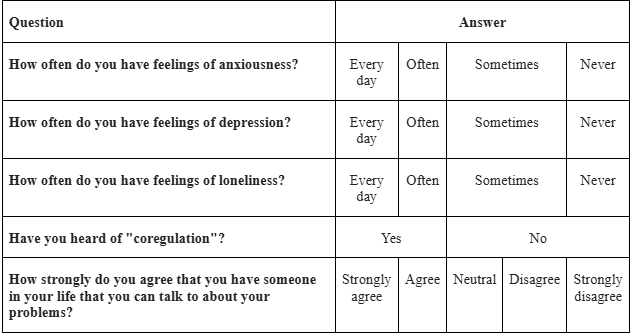

The first week consisted of administering a pre-test where girls answered a total of five questions. Questions measured the frequency of anxiety, depression, and loneliness using a 4-point Likert scale, in addition to measuring how strongly the girls agreed to having a confidant in their lives using a 5-point Likert scale, and their knowledge of key vocabulary words. Questions are listed below in Table 1.

Table 1. Pre-test and post-test questionnaire

These questions were also used for the post-test held at the end of the experiment. Following the pre-test, a lesson on social disconnection and loneliness ensued, followed by the effects of social disconnection.

Week two finished up the lesson on loneliness and disconnection, explaining the harmful effects of social disconnection and how to prevent it, ending with a brief lesson on what the Qur’an says about social disconnection. Due to unforeseen circumstances, the experiment was unable to be conducted for week three, prompting a change in the lesson plan.

Instead of having the girls perform an exercise on coregulation, week four was used as a discussion on social media. Girls were split into six groups of ten each and asked to answer the following questions on a piece of paper: “How do you think social media is affecting you?” and “How do you think social media is affecting those in your life?”. After answering these questions, the girls were given the post-test to wrap up the experiment. Results of the pre-test and post-test, in addition to the responses from week four’s discussion, were ultimately compiled and qualitatively evaluated to determine if the youth lesson plan from Coregulation Health Institute can be applied in a Muslim youth setting.

Results

For the first question of the interview, youth mentors from ICN’s middle school girls’ program responded that they would say that about 25% of the girls who attend the program exhibit some form of loneliness. They supported that by stating that since the girls are at an age where they form cliques and newcomers are often left out, the mentors encourage girls who sit by themselves to join groups where the girls are generally welcoming. Even after introducing them to these welcoming girls, those who desire to be lonely will continue to isolate themselves within conversations and group activities. In short, girls who sit alone want to stay alone; in other words, the quiet girls want to stay in their comfort zones. Another comment mentioned that mentors and attendees often see girls who constantly misbehave be more active in conversations and activities, perhaps indicating to the quieter and well-behaved girls that they do not receive the same attention as their counterparts do, and that life favors the rude and outspoken, rather than the polite and quiet girls. Regarding the second question, the mentors responded that all of ICN’s youth programs, including middle school, high school, college, and young professional programs, in addition to the program for adults aged 25 and over, are designed to foster conversation and establish a strong community. These programs are not limited to the geographic community of Naperville, Illinois; they are open to all who wish to attend. Regarding mental health, ICN Youth has affiliations with Manzar Health, a community-based research initiative addressing health and safety in the Muslim community, to create the Amal Program.

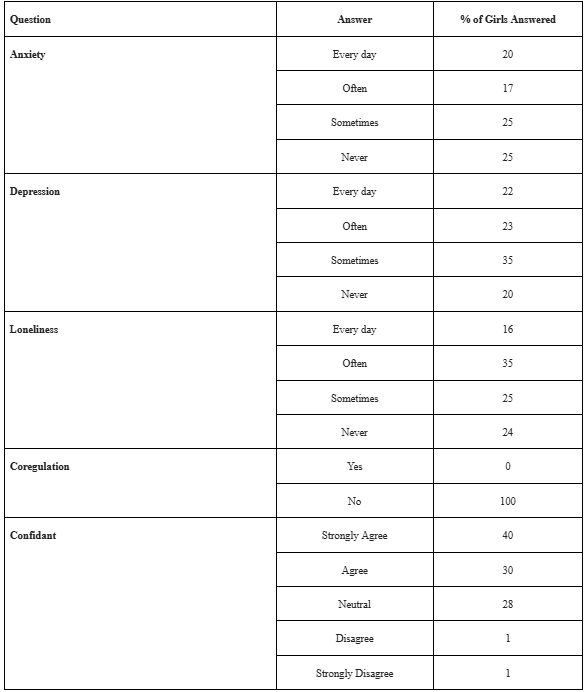

Representatives from the Amal Program often have events in the mosque for the youth, addressing any issues present in the community. Mentors did not have further comments regarding these questions. Regarding outreach to other mosques in DuPage and Cook County, only IFS responded back, stating that they have affiliations with the Khalil Center, a Muslim psychological and spiritual wellness center, and were not interested in other programs. For the experiment, the pretest revealed the following results, shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Percentages of each response from the pre-test

From week four’s discussion, the following answers were recorded as statements.

How do you think social media is affecting you?

Social media is an addiction and a distraction.

Social media makes me impatient, irritable, fidgety, and lazy.

Social media causes me to have a short attention span and have bad grades.

How do you think social media is affecting those in your life?

People in general are ruder; they speak to others in real life the way they speak to those online, bringing cyberbullying to real life.

Friends, family, and students ignore those speaking to them.

Parents are not as present and accessible.

Children are victims of “brain rot” (slang for mental decline due to excessive and trivial online content consumption).

Many people participate in trends, leading to overconsumption and waste.

The existence of social media influencers paints a false ideal narrative, which results in low self-esteem for the average person.

With AI (artificial intelligence) in social media and marketable personalities posing as professionals, there is confusion about credible information.

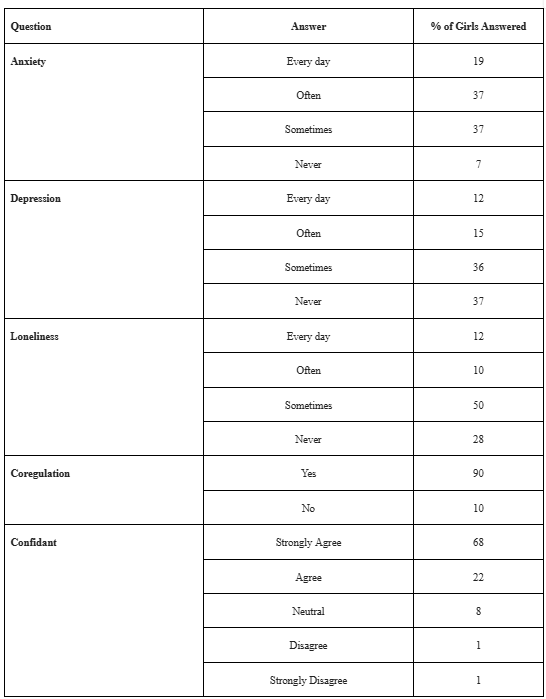

Table 3. Depicts the results from the post-test

Analysis

The interview with mentors of ICNY’s middle school girls program reveals that while the program focuses on group activities, it does not make a separate effort to address loneliness in the girls. Newcomers are encouraged to befriend more talkative girls and spend time with either girls they know from outside of the program or make new friends. Efforts are made by the team to ensure that girls are included, but they cannot control the dynamics of middle school girls. Despite their efforts, girls who do not want to befriend others or struggle with making friends and connecting with others remain this way throughout the duration of their time in the program.

The lack of response from other mosques could be due to many reasons. Perhaps staff do not check their emails regularly, or they did not find it necessary to respond. This implies that their silence was a lack of interest in engaging with Coregulation Health Institute’s proposed training.

Comparing the results of the post-test with the pre-test, we see that while the percentage of girls who answered “4” or felt anxious every day decreased from the pre-test to the post-test, the percentage for the middle levels of frequency increased, with the percentage increasing for the lowest frequency. This implies a change in the girls’ anxiety management skills, which led to a transition from high to slightly lower frequency, and the decrease in the lowest frequency indicates girls experiencing higher levels of anxiety. For depression, while the percentages of higher frequencies decreased, the percentages for lower frequencies increased. This indicates that girls were experiencing lower levels of depression by the end of the program. Similarly, percentages for higher frequencies of loneliness decreased while percentages for lower frequencies increased. This implies that girls were not feeling lonely as often, but this program did not have a significant impact, as the percentages of “every day” and “often” transformed into “sometimes” rather than “never”. There was a significant difference in the number of girls who were aware of coregulation from the beginning to the end of the experiment, indicating that the girls retained the information taught to them in the first two weeks. However, this does not prove that the change in frequencies from the pre-test to the post-test was a result of this retention because the number of girls varied per week. The girls who were present the first week may not have been present the other weeks, and the girls who were present the last week may not have been present the previous weeks. Lastly, the percentage of girls with the highest confidence in having a confidant increased from the pre-test to the post-test, decreased for those who simply agreed or were neutral, and remained the same for the lower confidence levels. This implies that the girls who were not as confident about having someone to share their problems with became more confident at the end of the program, while there were still a few girls who lacked a confidant.

From week four’s discussion, the girls indicated a strong sense of self-awareness through their answers. By stating that social media is an addictive distraction to them, which causes a negative change in behavior and negatively affects their performance in school, the girls illustrate their understanding that social media is a negative force for them. Lastly, from their responses on the effects of social media on those around them, the girls highlight social media’s negative impact on society. Girls expressed the detrimental effects of social media trends on themselves, their classmates, and their younger siblings, emphasizing the lack of intellectualism. They mention social media as being misleading, with the presence of social media influencers, AI, and regular individuals posing as professionals to promote consumerism and unhealthy habits. Lastly, social media was expressed as a barrier between friends, students and teachers, and families. This accentuates social media becoming a cause of social disconnection and loneliness. Children seeing their parents and friends spending more time on their devices than being present in conversation discourages them, leading them to isolate themselves and go on social media to receive the connection they lack in real life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while CHI’s guide for Christian Youth Group leaders is a very detailed and universally applicable guide, it is not very fitting for a Muslim middle school girls’ program that meets after school. The Muslim youth program at ICN aims to bring girls to the mosque and have them develop a love for going to the mosque through a brief Islamic lecture and group activities. As an after-school program, it does not have a lot of time to focus on aspects outside of topics the majority of girls express interest in or mentors find necessary. With an average attendance of 50 girls and only 6 mentors, it is difficult to ensure that every girl is engaged, participating, and taken care of. That is why quieter girls get left behind and appear to be less of a priority than the girls who are louder in volume and character. The results of the post-test reveal that perhaps there is a chance that the lessons of the Youth Group guide are helpful, but with the lack of time and resources, it cannot be accurately proven. It is hoped that the final discussion inspires the middle school girls to address their loneliness and social disconnection with regard to social media usage. In previous studies and initiatives, technology was used as a means of fixing an issue. However, in the case of the post-pandemic youth, technology has become the root of many issues. The Muslim youth are not safe from the effects of technology, which is why it was necessary to mention it as a part of the lesson plan. Ultimately, this may not prove to be feasible information regarding loneliness in the Muslim youth, but the girls now have an awareness of loneliness, social disconnection, and methods of identification and prevention.

Recommendations

This guide could prove to be universally applicable in targeting social disconnection and loneliness in the youth if it were applied for a longer period of time. Any time greater than three weeks could prove to be beneficial to the target group. Additionally, it is likely that an after-school approach may not be effective since children may be tired and burnt out from spending their day at school and may not have the means to pay attention after school. That is why it is recommended that this be applied for a weekend or summer program, making it easier for children to be engaged. Lastly, as suggested in a previous study, introducing the initiative to a member of the target age group with the intention of making them a co-producer of the program may make the program more appealing for that age group and garner more engagement.